The future of social media use during emergencies in Australia: insights from the 2014 Australian and New Zealand Disaster and Emergency Management Conference social media workshop

Dr Olga Anikeeva, Dr Malinda Steenkamp, Professor Paul Arbon

Abstract

Article

Introduction

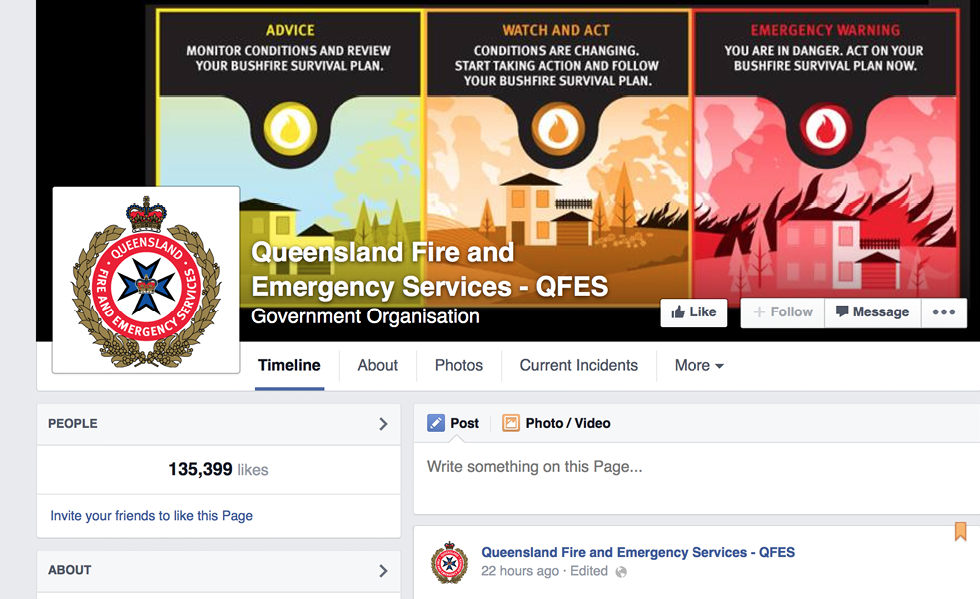

People are increasingly using social media during emergency events, such as bushfires, storms and floods (Bird, Ling & Hayes 2012, Cheong & Cheong 2011, CSIRO 2014, American Red Cross 2012, Latonero & Shklovski 2011). Information appears on platforms such as Twitter and Facebook in real time, frequently preceding traditional channels such as television and radio (American Red Cross 2012). Both in Australia and internationally, social media has been widely used to disseminate essential information and updates during emergency events. During the 2010-2011 floods in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, Twitter was used by emergency services, politicians, social media volunteers, traditional media reporters and community organisations to disseminate information to the affected communities (Cheong & Cheong 2011). One notable example is the use of Twitter and Facebook by Queensland Police when information and updates about the situation were provided to the community, sometimes as frequently as every few minutes. The platforms were used to control and respond to the spread of rumours and misinformation (Queensland Police 2013). An important advantage was that Queensland Police established their social media presence and strategy before the occurrence of the disaster, which ensured that clear processes for disseminating information and addressing rumours and misleading posts were in place and staff were familiar with the processes. This ensured that Queensland Police maintained their Twitter and Facebook presence throughout the disaster and were able to reach and respond to individuals who did not have access to traditional media channels due to power outages and water damage (Queensland Police 2013). Similarly, Brisbane City Council was able to effectively use social media platforms to disseminate information to their already well-established networks of followers. The Council’s dedicated social media resources and commitment to engaging in an open dialog with community members ensured that information was disseminated and evaluated in a timely fashion and questions and concerns were responded to, increasing community confidence (Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government 2011, Whitelaw & Henson 2014). Community-initiated Facebook groups were also established during this time, which gained an instant following from affected residents and their family and friends. These groups routinely posted information sourced from agencies such as the State Emergency Service and the Bureau of Meteorology to provide a comprehensive collection of updates to followers. Furthermore, group members used the platform to post eyewitness information, questions, requests for help and advice, thus establishing support networks within the affected communities and facilitating community engagement and involvement in providing assistance (Bird, Ling & Hayes 2012).

Brisbane City Council was able to effectively use social media platforms to disseminate information to their already well-established networks of followers.

Internationally, people are increasingly relying on social media during emergency events. A survey conducted by the American Red Cross found that mobile applications and social media are the fourth most popular way for Americans to obtain information during an emergency, following television, radio and online news. Social media is also widely used during emergencies as a source of emotional support and a method of obtaining information and advice about staying safe. Furthermore, Americans are increasingly expecting emergency agencies to monitor social media platforms (three quarters of survey respondents expected a response within three hours of posting a request for help on an organisation’s social media page) (American Red Cross 2012). The 2013 attack on Westgate Mall in Nairobi, Kenya illustrates the importance of social media during emergency events. Within moments of the attack, information and photographs were posted to social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, providing details of the location of the attack and the number of casualties (Mohammed 2013). While some early posts contained inaccurate information, such as incorrect locations and nature of the emergency, the community of social media users corrected misleading information, which ensured rapid correction of potentially misleading claims. The use of social media during this event enabled real-time dissemination of updates and warnings, instructing people to stay away from the mall and its surrounding area (Mohammed 2013). The warnings were supported with eyewitness accounts and photographs, which enabled the reliability of incoming information to be assessed by traditional media outlets and other organisations.

The Westgate Mall example illustrates that social media is not only an important tool that can facilitate the dissemination of information by emergency services agencies to communities; it can also alert these organisations to developing disasters and emergency events. Tools exist that enable more efficient analysis of incoming information and provide details on GPS coordinates, number of people affected and the assistance required. An example is the Emergency Situation Awareness tool developed by the CSIRO, which is designed to detect unusual activity on Twitter feeds and alert response agencies when an emergency or disaster is being broadcast and discussed online (Cheong & Cheong 2011). Despite the availability of such technologies, many emergency organisations have been slow to adopt and engage with social media. For this reason, a workshop at the 2014 Australian and New Zealand Disaster and Emergency Management conference provided a forum to discuss the current role of social media in the disaster and emergency sphere.

Social media workshop

The workshop brought together 21 participants from a range of backgrounds, including emergency services, academia and information technology. The main objective of the workshop was to discuss the current state and future development of social media in the emergency management field, highlight current facilitators and barriers to effective use of social media platforms, and suggest improvements and strategies for enabling the use of these technologies by both emergency services personnel and the public. This article outlines the three key themes that were discussed during the workshop.

1. The current state and future of social media use in the context of emergencies

Participants overwhelmingly agreed that social media use will become increasingly popular in the near future and the public will expect emergency services and response agencies to have and maintain an active social media presence. A number of participants commented that different social media platforms are likely to attract particular user groups and be more suited for certain purposes. For example, it was agreed that Twitter is best suited for broadcasting frequent updates and is particularly useful for those wanting to use social media to access up-to-date information. On the other hand, Facebook is well-suited to establishing online communities where users can share their own experiences, ask for help and provide assistance where needed. For this reason, participants suggested that emergency organisations would need to establish a presence across all major social media platforms. Participants agreed that it is likely that maintaining a strong social media presence will require dedicated staff and resources, with some suggesting that larger organisations may need to establish social media units or departments. Some participants expressed concern about the potential financial ramifications of employing additional staff and purchasing essential equipment required to maintain an active social media presence.

Posting information on Facebook in real time, frequently preceded traditional channels such as television and radio.

Participants also commented that the channels the public rely on to obtain information about unfolding emergency events are changing. While television, radio and telephone hotlines were previously the most trusted and widely used means of accessing accurate information, it was suggested that the formation of social media networks will contribute to a shift towards increasing reliance on eyewitness accounts and reports provided by other users. However, some population sub-groups, such as the elderly and unemployed, may be less likely to have access to mobile phone and online communications. Therefore, emergency communications need to be tailored to individual communities and reflect their unique population composition and characteristics (Boon 2014). Participants questioned how the accuracy and reliability of information can be assessed on social media, with some suggesting that new, rapid methods of moderation, validation and verification need to be established and used to limit the amount of misinformation or deliberately misleading reports. A closely related concept was the development and refinement of technologies that enable organisations to efficiently sort through the vast amount of incoming information to extract the key messages and filter out unnecessary ‘noise’.

Finally, a number of participants suggested that increased use of social media is likely to contribute to greater community interaction, by enabling community members to comment on, contribute to and provide feedback to emergency services and response agencies about their plans and actions. Social media can contribute to greater feelings of connectedness among residents and their local emergency services and can lead to the establishment of a stronger and more inclusive community voice. However, consideration must be given to the extent to which various community members are likely to participate in discussions. It is likely that some individuals, such as the elderly, those with low English proficiency or low socio-economic status, may be underrepresented in community social media networks and discussions.

Twitter: suited to broadcasting frequent updates

Facebook: suited to establishing online communities

2. Current and future possibilities and opportunities for social media use in the emergency context

Participants agreed that the expansion of social media use within organisations needs to be supported by a national strategy to guide the development of plans and policies, support long-term objectives and increase organisational commitment. A national social media strategy for organisations may address current resistance to social media use in some settings, which some participants believed may in part be explained by generational differences in attitudes towards social media uptake. Participants stated that it is important to identify and support social media champions within organisations in order to drive change, which may be easier to achieve with a national strategy that encourages social media uptake.

Participants also commented on the opportunity to create a more diverse community of social media users. Many agreed that social media uptake is lower among certain population sub-groups, such as older individuals. Methods of encouraging participation by demonstrating benefits and making the platforms relevant to various population sub-groups need to be developed. One example during the workshop was the expanding use of health technologies, such as blood pressure monitors, that are compatible with smartphone applications and allow users to track changes over time and set goals and reminders. Such targeted technologies are likely to encourage greater use among older individuals. Similar tactics could be employed to demonstrate the utility of social media platforms for this group, such as greater social connectedness and increased participation in community discussions. Importantly, barriers to social media use, such as cost or lack of time need identification and addressing to ensure a diverse population of social media users.

A number of participants commented on the possibilities that stem from increasing use of GPS technology that provide tailored, location-based information to be delivered to target groups. This technology allows organisations to send warnings, alerts and other critical updates to individuals in specific physical locations, thus increasing the information relevance.

Queensland Police used their Facebook presence to reach and respond to individuals who did not have access to traditional media channels.

3. Current enablers and barriers to effective use of social media in the emergency context

During the final part of the workshop, participants were asked to identify factors that facilitate or hinder the effective implementation and use of social media by emergency services organisations and the general public. One of the key barriers identified was the lack of dedicated staff and additional resources required to establish and maintain a strong social media presence. Participants commented that the majority of organisations lack dedicated social media staff and the responsibility of maintaining the organisation’s social media presence (whether through an organisation’s own social media account or by active participation in existing social media networks) is given to those with a special interest in this technology, who then must find time for social media responsibilities around their primary job.

Another potential barrier is the possibility of network failure during emergency or disaster events, particularly in remote areas with poor network coverage. Participants suggested that this barrier may be overcome by developing technologies that enable individual mobile phones to link to each other to ensure coverage is not lost and people are able to access social networks to receive critical updates when they are needed most.

One key advantage of social media platforms discussed was that they tend to be more robust than standard websites and less likely to fail during periods of high traffic, which may occur during emergency events. The capability of social networking platforms to effectively deal with high volume traffic in a cost-effective way means that critical information and updates can potentially be disseminated to large numbers of people and their networks.

Participants also considered the potential consequences of incorrect or deliberately misleading information being broadcast via social media channels. They identified a lack of clarity with respect to who would be held responsible for any consequences arising from such misinformation. In particular, participants felt this might be a deterrent for organisations to maintain a social media presence if they are held responsible for false information posted by others that they fail to rapidly evaluate and remove from their social media profiles. Participants suggested the need for clear policies and guidelines to protect organisations.

It was agreed that dedicated social media training could help organisations to see the merit in establishing and maintaining a social media presence. Participants suggested best-practice local and international examples could be used for training purposes. They believed that this would reduce the amount of trial-and-error that frequently accompanies social media adoption in the absence of dedicated guidance and training, which can act as a deterrent for organisations, particularly those that are under-resourced.

Participants considered that engaging volunteers in social media roles could address the financial and resource barriers to adoption of social media. It was suggested that after receiving initial training and guidance in appropriate social media use, volunteers could play a key role in monitoring social media platforms, posting updates and engaging with the wider community. This approach could potentially have the additional benefit of attracting a greater number of volunteers with a particular interest in social media and community engagement.

Conclusion

Social media platforms are powerful two-way tools that can be used to rapidly disseminate information and expose developing emergencies through ongoing monitoring of social media feeds. Despite the advantages and examples of effective use both locally and internationally, many organisations have been reluctant to adopt these technologies and maintain an active social media presence. The workshop highlighted important enablers and barriers to social media use within emergency and response agencies. Clear guidelines, adequate training, engagement of volunteers in social media roles, ongoing support and strategies for dealing with rumours and misinformation are likely to encourage greater uptake of these platforms in the emergency and disaster sphere.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the workshop participants for their insightful comments and Ms Liana Formichella for conducting the background literature searches.

References

Bird D, Ling M & Haynes K 2012, Flooding Facebook - the use of social media during the Queensland and Victorian floods. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 27-33.

Boon H 2014, Investigating rural community communication for flood and bushfire preparedness. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 17-25.

Cheong F & Cheong C 2011, Social media data mining: a social network analysis of tweets during the 2010-2011 Australian floods. PACIS 2011 Proceedings. Paper 46.

CSIRO 2014, Emergency situation awareness tool for social media. At: www.csiro.au/Outcomes/ICT-and-Services/emergency-situation-awareness.aspx.

American Red Cross 2012, More Americans using mobile apps in emergencies. At: www.redcross.org/news/press-release/More-Americans-Using-Mobile-Apps-in-Emergencies.

Latonero M & Shklovski I 2011, Emergency management, Twitter and social media evangelism. International Journal of Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, 3(4), pp. 1-16.

Queensland Police 2013, Social media case study. At: www.police.qld.gov.au/corporatedocs/reportsPublications/other/Social-Media.htm.

Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government 2011, Case study on social media use in emergency management. At: www.acelg.org.au/case-study-social-media-use-emergency-management.

Mohammed O 2013, How the Nairobi mall attack unfolded on social media. Global Voices Online. At: http://globalvoicesonline.org/2013/09/23/how-the-nairobi-mall-attack-unfolded-on-social-media/.

Whitelaw T & Henson D 2014, All that I’m hearing from you is white noise: social media aggregation in emergency response. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 48-51.

About the authors

Dr Olga Anikeeva is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Torrens Resilience Institute at Flinders University with a background in public health and epidemiology.

Dr Malinda Steenkamp is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Torrens Resilience Institute at Flinders University. She has a background in epidemiology, public health and maternal and infant health.

Professor Paul Arbon is the Director of Torrens Resilience Institute at Flinders University and current President of the World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine. His research focuses on disaster resilience and the health aspects of disaster response and recovery.