It is widely acknowledged that community-led initiatives can significantly improve community resilience to bushfires and other disasters. These initiatives can be particularly important in overcoming some of the challenges presented to emergency management organisations in moving towards the goal of community resilience and shared responsibility. This paper provides an overview of a case study of the roles and outcomes of community-led bushfire and disaster resilience initiatives in the region of Kangaroo Valley, New South Wales, Australia. Three initiatives are described: the establishment of a comprehensive network of bushfire-ready neighbourhood groups, the establishment of the Kangaroo Valley Bushfire Recovery Association and its recovery ‘drop-in centre’, and the genesis and evolution of a community resilience group known as ‘Resilient KV’. These initiatives played significant roles before, during and after the disastrous passage of the Currowan bushfire through Kangaroo Valley in January 2020. This fire destroyed over 10% of homes in the region and had very severe impacts on people, infrastructure, animals and the environment. The findings of this study covered issues including household ‘stay-and-defend’ versus ‘leave early’ decision-making and the ways residents improved the bushfire resilience of their properties.

Background

During the southern hemisphere spring and summer of 2019–20 a bushfire crisis unfolded across several Australian states and territories that was unprecedented in terms of the number, size and intensity of the bushfires that occurred and their geographical extent. The catastrophic effects of these ‘Black Summer’ bushfires led to individuals, families, communities and resources being stretched as never before. This applied to the agencies responding during the fire emergency, to organisations assisting affected communities during their recovery and to the reconstruction industry that was responsible for the demolition of destroyed and damaged buildings and infrastructure and the eventual rebuilding of people’s homes and other property.

This paper provides an overview of some of the outcomes of the study ‘Building Community Resilience to Bushfires: A Case Study of Kangaroo Valley, Australia’. The aim was to understand the complex, multi-level, multi-disciplinary issues that influence the bushfire resilience of communities via a case study of the Kangaroo Valley community located in New South Wales, which was hit by the Currowan fire on the night of 4 January 2020.

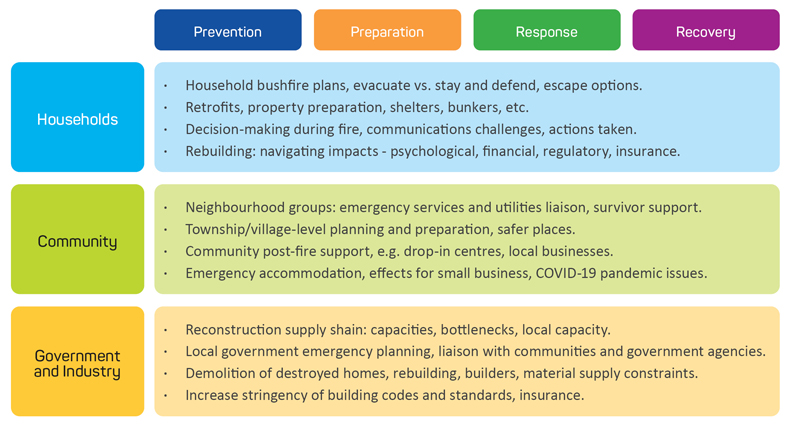

We were interested to explore bushfire risk prevention, preparation, response and recovery approaches and activities in relation to the 3 societal levels as shown in Figure 1 (i.e. ‘Households’, ‘Community’, and ‘Government and Industry’). Some of the specific issues covered in the study included:

- the roles that new community-led initiatives played in each phase of the event

- household preparation for, response to and recovery from the Currowan fire, including their leave or stay-and-defend decision-making and retrofitting of their homes

- how the reconstruction and supply chain ecosystem operated.

Figure 1: Schematic of societal layers influencing community bushfire resilience explored in this project.

From the overall study, we developed a number of information resources for community and practitioners, including a final report (McKinnon et al. 2022), a webinar and a series of 9 Bushfire Research Briefs that describe pertinent issues in detail (McKinnon et al. 2024).

Data collection was primarily through 70 semi-structured, in-depth interviews involving over 83 interviewees. These were supported by a review of written materials. Cohorts of interviewees included:

- residents and householders living in and around Kangaroo Valley

- community members involved in bushfire resilience initiatives

- local business owners

- volunteers and employees of emergency services and not-for-profit organisations

- employees of local government

- local professionals with relevant expertise, such as bushfire consultants

- people involved in the post-bushfire reconstruction program (e.g. peak body representatives, architects and designers, builders, tradespeople, demolition contractors).

In addition to data gathered through interviews, technical bushfire resilience assessments were made of 37 homes and other buildings to investigate the standard of construction of existing dwellings and retrofits undertaken by householders to increase the resistance of their property to bushfires. This aspect of the project was informed by previous research on the retrofitting of homes (e.g. Penman et al. 2017).

In this paper we focus on the genesis and evolution of local community-led bushfire resilience initiatives in the Kangaroo Valley. Research by Lucas et al. (2022) demonstrated the importance of developing ‘… social adaptation pathways using local communication interventions to build the neighbourhood knowledge, networks and capacities that enable community-led bushfire preparedness’. This can be achieved via a range of community strategies and approaches that provide stronger connections within the micro-level community of households and businesses, and to the macro-level of government, emergency services and the not-for-profit sector, as discussed by McLennan et al. (2021), Pope and Harms (2022) and Bloor et al. (2023).

Kangaroo Valley and the Currowan bushfire

Located 2 hours’ drive southwest of Sydney, Kangaroo Valley is a semi-rural area of approximately 256 km2 with a population of around 900 people in 500 households. It is a popular tourist destination and the population increases substantially during summer months. The region is bordered by national parks and nature reserves, particularly the Morton National Park to the south and west. This, together with the geography of the valley itself means that road access to the area is limited, which has important implications for residents and authorities in the event of a major incident such as a bushfire or other emergency. Evacuation may become difficult if any of the roads leading to the area become impassable.

The Currowan fire is believed to have been ignited by a lightning strike approximately 90 km southwest of the valley on 25 November 2019 (Adcock 2021). It eventually burned for 74 days across 320,385 hectares. The firefront reached Kangaroo Valley during the afternoon of 4 January 2020. The Nowra weather station, 24 km away, measured air temperatures over 43°C and wind speeds over 55 km/h that day, but participants we interviewed described much more intense local winds and temperatures.

The Kangaroo Valley community was significantly affected by the Currowan fire, which destroyed approximately 50 homes, representing 10% of all homes. In addition, many holiday cabins, sheds and other buildings were destroyed, along with equipment and extensive infrastructure. Many thousands of animals died, including livestock. The loss and damage to property, effects on mental health and wellbeing, economic effects for individuals, businesses and the community, the death of animals and significant damage to ecosystems have all presented long-lasting challenges for the community.

Pyrocumulonimbus cloud looming over Kangaroo Valley on 4 January 2020.

Image: Maureen Bell

Local community-led initiatives prior to the Currowan fire

As with many bushfire-prone communities, members of the Kangaroo Valley Volunteer Rural Fire Brigade (KVVRFB) have provided support to their community in both bushfire fighting capabilities and community engagement over many decades. During the autumn and winter of 2018, it became clear that bushfire risks in Kangaroo Valley and surrounding regions were increasing beyond historical expectations due to low rainfall and high fuel loads. As a result of such concerns, the captain of the KVVRFB and others, including the local police officer, organised a Public Bushfire Awareness Community Meeting in September 2018, which was attended by approximately 150 people, including residents and members of NSW Rural Fire Service (NSWRFS). In addition to achieving heightened community awareness of these higher risks and the need to prepare for possible future bushfires, another key outcome of the meeting was a call by the KVVRFB for the community to ‘… take the lead in developing a Community Bushfire Survival Plan for Kangaroo Valley’ (Smart 2018).

Kangaroo Valley Community Bushfire Committee

Following this public meeting, a new entity was established of the Kangaroo Valley Community Bushfire Committee (KVCBC), with members having a variety of backgrounds and experiences, including NSWRFS volunteers, local trades people, academics, logistics specialists and lawyers. A wide range of issues and concerns were canvassed including a perceived lack of awareness, planning and preparation of many households regarding bushfires, issues with large numbers of tourists and visitors during bushfire danger periods, the lack of signage regarding bushfire danger in the area, potential evacuation advice and actions, residents’ leave-or-stay intentions in the event of a bushfire, vulnerable members of the community, and potential effects of bushfire on businesses, agriculture and stock.

KVCBC analysed existing bushfire plans for the local government area and were of the view that these were too general to address the specific geography and local infrastructure and assets of the valley. They developed a discussion paper relating to the development of a community bushfire plan that identified specific vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure and began discussions with local government and emergency management organisations, including the NSWRFS. Drawing on models developed in other bushfire-prone regions, the KVCBC advocated for a 4-level approach to community organisation in Kangaroo Valley, namely: 1) individual households, 2) neighbourhoods, 3) larger localities and 4) community-wide level.

These efforts created new networks of information sharing between the community, local government and emergency services. Although good progress was made, some interviewees reported that this was not without some challenges, especially in the early phases of KVCBC’s advocacy for changes to local disaster plans on the basis of local knowledge and expertise. This aligns with the experience of other community-led resilience groups, as described by McLennan et al. (2021) in their case studies of ‘outsider emergency volunteering’ and the potential clash of cultures between that of emergency services organisations and community-led groups as analysed by Rawsthorne et al. (2023). Nevertheless, increasing trust and collaboration between community resilience groups and emergency management organisations was subsequently successfully developed, particularly during and since the Black Summer bushfires.

The Bushfire-Ready Neighbourhood Planning information stall at the 2020 Kangaroo Valley Agricultural Show.

Image: Paul Cooper

Bushfire-Ready Neighbourhood Groups Network

Following the establishment of the KVCBC and other discussions within the community, the first Bushfire-Ready Neighbourhood Groups were established in the Upper Kangaroo River area of the region. At a local community meeting, a ‘grassroots up’ participatory process was used to agree on the locations and boundaries of 9 neighbourhood groups, each with a neighbourhood coordinator and deputy. A significant number of documents, maps, knowledge and other resources were developed by members of that community and shared with other groups that were subsequently established in the wider Kangaroo Valley area during 2019. Development of household bushfire survival plans was strongly encouraged and facilitated, for example, by sharing specific examples of plans already developed by knowledgeable residents. This was later described by one interviewee as having ‘… dramatically helped people get over the line of developing their own bushfire plan’. A WhatsApp group was formed to cover each of the 9 neighbourhoods and, given the lack of mobile phone reception in the area, all Upper Kangaroo River neighbourhood coordinators purchased their own UHF/CB radios to improve communications between groups in the event of power and/or telecommunications failures.

In the months and days before the Currowan fire, a number of other Bushfire-Ready Neighbourhood Groups were formed and very many, if not all, neighbourhood groups met face-to-face in the anxious lead up to the fire. Residents, together with representatives of KVVRFB and/or KVCBC, discussed the challenges facing them. This included listening to frank advice from local experts on the risks of staying to defend properties, finalising household bushfire survival plans and assembling contact details for all residents. One comment was:

That [neighbourhood] meeting, [my partner] and I said it, I don’t know how many times, that meeting saved countless lives, in our opinion. [A local RFS member] went through what to expect for the fire, how horrifying the experience would be, how difficult it would be for someone to defend their property unless they were completely fully resourced and had everything in their favour, and even then they may not be able to. He went through the ferocity of the fire, that it could be 1,000 degrees Celsius, that it would be pitch black like night, that the roar of the fire and the wind would be so extreme you won’t be able to hear each other communicate, hence why you need to have everything written down and rehearsed.

(Resident)

During the week immediately prior to the arrival of the fire, an intense effort was made by the Bushfire-Ready Neighbourhood Groups to assemble a database of the stay-or-leave intentions of all residents in localities covered by neighbourhood groups. This information, together with detailed maps of many of the neighbourhood group localities, was provided to the KVVRFB. This meant that fire crews, both locally and from other districts, and other emergency personnel, would be aware of the location of people who planned to stay and defend rather than evacuate early. Checks on such households were prioritised by fire crews and other emergency services in areas hit by the fire in the hours after it passed. Data from the interviews indicated that this process was seen to be extremely important and of great value to both the community and emergency services.

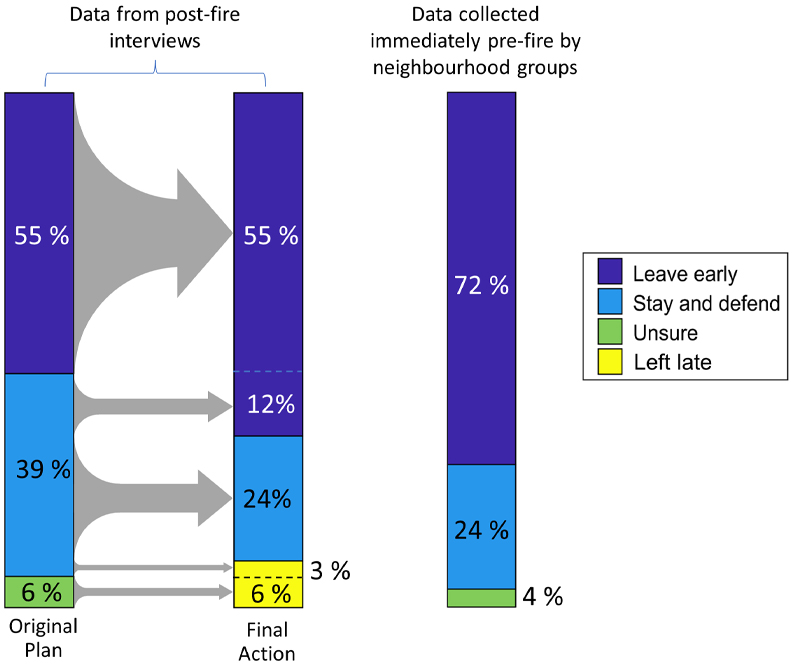

All 33 households that were interviewed in this case study had established some form of bushfire survival plan prior to the Currowan fire, although they varied widely from unwritten vague intentions through to well-documented plans addressing multiple scenarios. The 55% of households that originally intended to evacuate prior to the fire did so, typically some days in advance. A smaller proportion (39% of interviewees) planned to stay and defend, but about one third of these changed their plan in the weeks preceding the Currowan bushfire and eventually evacuated early because the perception of abnormally severe risks. Data collected by neighbourhood coordinators immediately before the fire aligned closely with that gleaned from the interviews. Figure 2 shows the reported original stay-or-leave intentions of interviewees (n=33) and their actual actions prior to the fire. The right column shows data provided by residents (n=401) to Group Coordinators prior to the Currowan fire.

An important finding was that the proportion of householders interviewed were uncertain whether to stay or leave before the arrival of the fire was lower than that reported for many other fires. For example, in a survey in the aftermath of the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires it was found that 26% of the 1,314 respondents were effectively undecided about what to do prior to the fires (Whittaker et al. 2013). It seems possible that the many efforts to get residents to develop a firm bushfire survival plan and the relatively long lead time before the arrival of the Currowan fire had positive consequences for the clarity of householder leave-early or stay-and-defend decision-making, though it is not possible to definitively validate this hypothesis.

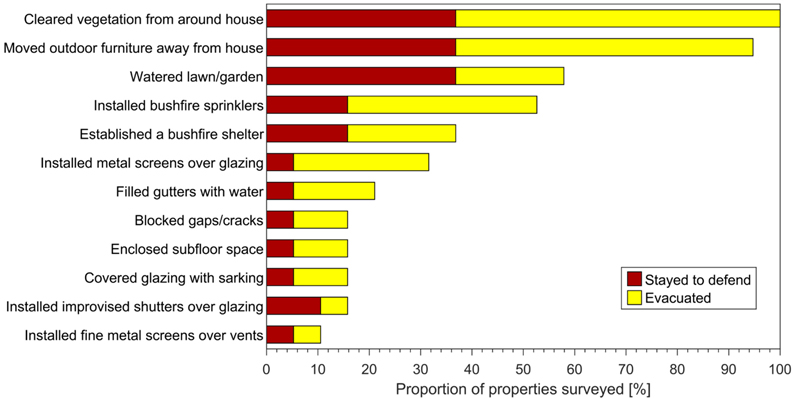

Many residents recognised the elevated level of danger early in the fire season as the Currowan fire grew in the south through November and December 2019. This forewarning allowed residents to make plans, clear vegetation and retrofit buildings. Many of the residents interviewed undertook substantial works on their properties in the weeks leading up to the arrival of the fire. Details of the types of preparations and retrofits undertaken are summarised in Figure 3. All of the assessed householders had prepared the area surrounding their houses (e.g. by clearing vegetation, watering and moving outdoor furniture), whereas a smaller group (35%) undertook more extensive retrofit works on their homes and other buildings.

Figure 2: Householder leaving versus stay-and-defend intentions prior to arrival of the Currowan fire.

Community-led response and recovery: the recovery drop-in centre

While there were no specific plans for a community-led recovery prior to the arrival of the fire, in the immediate aftermath, fire a new community-led bushfire emergency recovery group was quickly established, and within 3 days a recovery centre was set up in a shopfront in the village. From the interviews with residents and other stakeholders, it was clear that the recovery drop-in centre was critically important to the many significantly affected residents. Interviewees reported government and not-for-profit agencies were overwhelmed by the massive scale of the aftermath of the fires and were unable to provide substantial assistance at the local level for many weeks. The initial organic process of developing the drop-in centre was formalised through the establishment of the Kangaroo Valley Bushfire Recovery Association (KVBRA). An online GoFundMe fundraising campaign was established immediately after the fire and raised over $44,000 in a month. These funds were donated to the local volunteer rural fire brigades and to the KVBRA. A further $65,000 was raised for KVBRA via a fundraising dinner and auction shortly after.

Local volunteers at the KVBRA drop-in centre were quickly able to help people locate places to stay, contact their insurers and banks and apply for funds from charities and government sources, among many other important initiatives. The success of the recovery centre was, in part, due to the broad skillsets and commitment of the volunteers and good advice from members of the community and colleagues with prior bushfire recovery experience. It was also a place to share experiences with other residents and to receive emotional support through community connections. Complementing the drop-in centre was a community wildlife initiative to care for affected livestock, domestic animals and wildlife.

The drop-in centre was widely praised by the research participants and it offers a powerful example of how individuals with the necessary commitment and skills can provide practical and psychosocial support to their community and make a substantial post-disaster difference.

Figure 3: Summary of property preparation and home retrofits undertaken on the Kangaroo Valley properties assessed (n=19).

Ongoing evolution of disaster resilience initiatives

As recovery efforts continued following the Currowan fire, together with the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and a number of significant rain events, members of the Kangaroo Valley community sought to formalise and consolidate previous activities and initiatives.

It became clear that a single entity focused on disaster resilience would be beneficial, rather than multiple entities dealing separately with pre- and post-disaster phases, and with a broader focus than bushfire resilience alone. In addition, initiatives such as the KVBRA had always planned for a limited lifespan. So there was a desire to not lose the invaluable experience and lessons learnt from the initiative. Thus, a new incorporated body was formed and launched in November 2023 as the Kangaroo Valley Community Association for Disaster Resilience, known as ‘Resilient KV’. The scope of this organisation was broadened to cover all types of natural hazards and all phases of the emergency management cycle, in contrast to the original focus on prevention and preparation for bushfires. Resilient KV continues to facilitate the Neighbourhood Groups Network and fills the gap left by the dissolution of the KVBRA. Advantages of formal incorporation/consolidation of the previous community-led organisations has also included the ability to obtain funding from government and elsewhere, and to purchase insurance cover.

Planning is underway to implement a Kangaroo Valley recovery drop-in centre should another major bushfire or other event occur. This includes addressing some of the challenges that were experienced after the Currowan fire, such as prearranged agreements for use of suitable premises, liaison with stakeholders (local municipal council), volunteer training (e.g. in administration, IT and data management) and training in trauma-informed support of people and the wellbeing of volunteers.

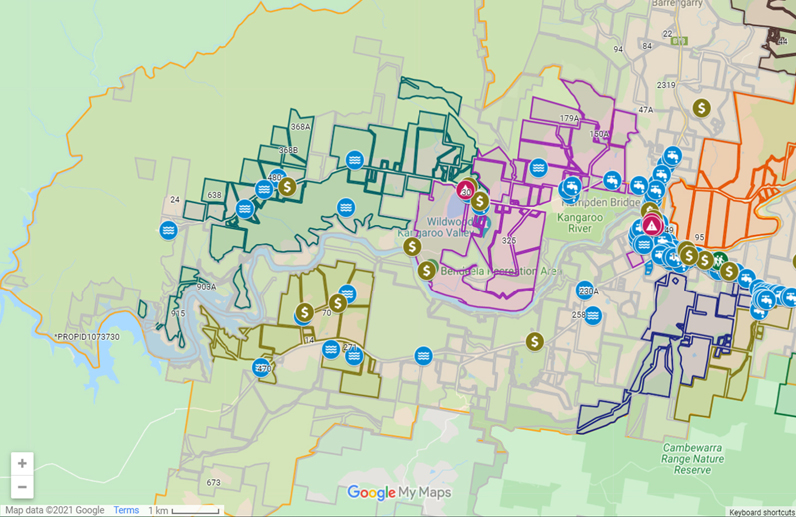

Resilient KV is continuing to develop a Kangaroo Valley Bushfire Preparedness Map. This was initially developed by a small group of KVCBC and community members using Google Maps as the primary source of geospatial information, with community members providing local information data layers such as hydrants, static water supplies, community assets and risks (Figure 4). This initiative has parallels with bushfire preparedness ‘participatory mapping’ activities documented by Haworth et al. (2016).

The network of Kangaroo Valley Neighbourhood Groups has continued to evolve and is now more closely linked with the KVVRFB. Senior KVVRFB officers are members of a Neighbourhood Coordinators WhatsApp group that facilitates closer 2-way sharing of information.

Figure 4: A pilot online Kangaroo Valley Bushfire Preparedness Map showing boundaries of properties, neighbourhoods and localities along with hydrants (tap icons), static water sources (ripple icons), infrastructure and assets ($) and hazards (∆).

Summary

This case study of Kangaroo Valley provides examples of community-led resilience initiatives arising through the preparation, response and recovery phases of a significant bushfire event. It also covers the evolution of those activities as the recovery efforts blend into preparation for future events. The resounding sentiment among interviewees was that such initiatives were essential to the community’s resilience during and after the Currowan fire and that they likely saved lives. While the Kangaroo Valley approach may not suit the contexts, resources or capabilities of all communities, its elements can be adopted and adapted for other communities.